Counterfeits: the Importance of Knowing Your Money

Central banks differ in their approach to the withdrawal of banknotes with old designs once new versions are issued. A period of co-circulation is inevitable, after which banks have a choice between allowing co-circulation of old and new or rapidly withdrawing the old notes (which it may decide to do when redenomination is involved or to replace a series that has been subject to large-scale theft or counterfeiting). But whereas some issuing authorities offer a period of a few months to a year before the old versions cease to be legal tender, many others allow the two versions to co-circulate indefinitely – with old notes only withdrawn when they are unfit. The second approach makes sense financially – after all, why withdraw notes when they are still fit? But less sense in terms of security; since new designs are generally brought out to combat counterfeits, it seems somewhat perverse to then continue circulating their less-secure predecessors. The recent case of counterfeiting in South Africa appears to bear out the dangers of the latter approach.

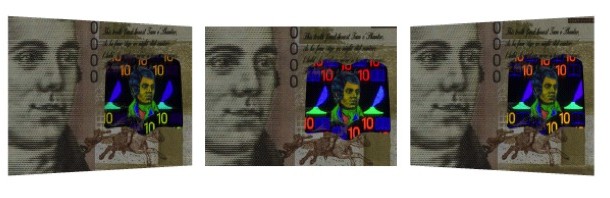

Earlier this year, ‘very genuine-looking’ R200 counterfeits started circulating. The Consumer Goods Council of South Africa warned the public to be on the lookout for the fakes. It stated that the counterfeits were ‘high quality’, even down to their luminescent features’, and it was the quality of the counterfeits, rather than their quantity (estimated to number around 5,000), which was causing concern. To identify the counterfeits, the Council advised the public to examine three different features (circled in red in the image) – all produced, in the real version, with intaglio. First was the round circle above the braille dots: a real note has fine, clear lines running through it, while in a fake note the lines are blurred. Second was the leopard’s head on the bottom right hand side of the note. It overlaps the flower and leaves, within which are fine green lines. Fakes have almost fully green leaves with blurred lines. And third, to the right of the leopard’s head, the micro-lettering should read South African Reserve Bank. The Council also advised the public to pay attention to the distinct feel and sound of a genuine banknote: the rough feel of the intaglio printing and the crackling sound of the paper when handled. Clear enough. But what was apparently not so clear – to retailers as well as the public – was that there are actually two banknote series in circulation: the old series issued in 1994, and the upgraded series of 2005. Only the old R200 was being counterfeited, but many people believed that all R200 notes were in danger. When, as result of the counterfeits, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) announced that all old series R200 notes would be withdrawn from circulation and cease to be legal tender on 31 May 2010, many shops, restaurants and petrol stations – not to mention government post offices – over-reacted by refusing to accept any R200 notes. This reaction highlighted the fact that retail staff were not trained well enough or sufficiently informed to confidently tell the difference between the old and new series – something which was actually relatively easy to do, as the new series carried highly distinguishable security features, such as OVI®, a security thread and an iridescent band. If retail staff could not distinguish between the new and old series, it was reasonable to assume that they would not be able to distinguish real from fake either. Hence the preference by retailers to refuse all R200 notes, even if it meant losing business.

“Know Your Money†Campaign

In its bid to familiarise the public, retailers, traders and commercial banks with the appearance and features of the upgraded R200 note, the SARB launched a “Know your Money†awareness campaign. To reach as many people as possible, posters clearly describing each security feature were inserted in all Sunday newspapers. In addition, information pamphlets were distributed to World Cup visitors at all international airports.

The posters to support the ‘Know Your Money’ awareness campaign

The posters to support the ‘Know Your Money’ awareness campaign

The SARB also decided to extend the deadline to 31 July for withdrawal of the old R200 series, by which time the World Cup would have been over.

The situation was therefore resolved … at least as far as the R200 was concerned.

Higher Losses from Fake R100 Notes

In the meantime, however, four men had been arrested for apparently using fake R100 bills, and a number of complaints started to come in that the old series R100 was also being counterfeited. Indeed, some commercial banks were experiencing higher losses from fake R100 notes than from R200 notes. And some of these fake R100s were copies of the new series, although happily not very good ones. They carried a strip of aluminium foil that imitated the security thread, but that peeled off easily with a fingernail; and they did not even try to imitate the other visible security features, such as watermark, OVI® numeral, and iridescent band. This showed that the 2005 South African banknote series was continuing to hold its ground against the counterfeiting onslaught. Nevertheless, the issue remains, not only in South Africa but worldwide, that unless a nation really ‘knows its money’, even poor quality counterfeits will find a way to slip into circulation. It also shows the perils of co-circulating old and newer versions of the same note. This point is made by the Bank of Canada’s recent successful campaign to bring down levels of counterfeits which involved, among other measures, the speedier withdrawal of notes in the old series. Furthermore, the public is already notoriously hazy about recognising the features on their notes, as various reports have shown. The process becomes a whole lot harder when there is more than one type of note to recognise.

Central banks should take note, because continuing to co-circulate different versions may be cost-effective, but could end up being a false economy.