Why Does Cash in Circulation Continue to Grow

07 April, 2013

One of the fundamental questions on the minds of everyone involved in the payments industry - If there is more competition for cash as a payment device now than ever before, why does cash in circulation continue to grow?

It would seem that anyone asked that question has an answer, yet no matter how much thought they have devoted to the subject the vast majority of them, myself included, missed on critical element. That factor is so important at this fragile stage in the world economy that it could be argued to represent job security for those of us who derive our living from currency management.

Many articles and editorials have crossed our desks espousing different theories on the cycle and longevity of cash as a payment device. In particular every single player in the alternative-to-cash payment arena – Visa, Mastercard, American Express, PayPal, Union Pay, BitCoin, etc. – has research purporting to indicate the predictable demise of cash. As I was reading a recent essay authored and presented by Mr. John C. Williams, President and CEO of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank I came to understand that in the arena of payments instruments, the largest player is rarely involved in any industry discussion or active stewardship. Many decades of global availability and global payment acceptance have made the American Dollar the premiere payment and value storage mechanism of choice for societies in stress. It is the effect of political instability and financial market uncertainty to which I (in this editorial) and Mr. Williams (in his essay) theorize is a significant motivating factor in answering the question, “why does cash in circulation continue to grow?”. I offer the following from Mr. Williams essay:

Many articles and editorials have crossed our desks espousing different theories on the cycle and longevity of cash as a payment device. In particular every single player in the alternative-to-cash payment arena – Visa, Mastercard, American Express, PayPal, Union Pay, BitCoin, etc. – has research purporting to indicate the predictable demise of cash. As I was reading a recent essay authored and presented by Mr. John C. Williams, President and CEO of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank I came to understand that in the arena of payments instruments, the largest player is rarely involved in any industry discussion or active stewardship. Many decades of global availability and global payment acceptance have made the American Dollar the premiere payment and value storage mechanism of choice for societies in stress. It is the effect of political instability and financial market uncertainty to which I (in this editorial) and Mr. Williams (in his essay) theorize is a significant motivating factor in answering the question, “why does cash in circulation continue to grow?”. I offer the following from Mr. Williams essay:

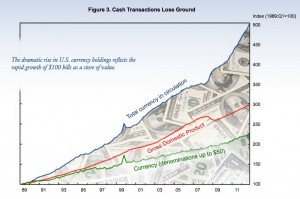

The U.S. financial crisis ended in 2009, and confidence in banks has largely returned. So, why have cash holdings continued to rise? One reason is that interest rates are very low in the United States and many other countries, dramatically lowering the opportunity cost of holding cash. In December 2008, the Federal Reserve lowered short-term interest rates close to zero, and they have remained low since. As a result, checking and short-term savings accounts offer extraordinarily low interest rates, if they pay anything at all. People have little incentive to put cash back into the banks.

But there’s more to the story. Demand for U.S. currency is not only affected by events at home. What happens in other countries is also important. Europe’s financial crisis has played a powerful role in driving demand. As Europe’s crisis worsened in the spring of 2010, U.S. currency holdings rose sharply. And they continued to rise as economic and political turmoil and uncertainty about the future sent Europeans scrambling to convert some of their euros to dollars. According to one estimate, the share of U.S. currency held abroad rose from about 56% before the tumultuous events of the past five years to nearly 66% in 2012.

A possible expansion of this theory could add to our understanding as to why other internationally exchangeable currencies are also seeing increases in circulation volumes. As the research would appear to support, there is a growing demand for high denomination notes for purposes of value storage, easy portability and anonymity.

Why are holdings of currency soaring at the same time that Americans appear to be turning away from using cash to pay for purchases? To make sense of this paradox, it’s helpful to understand the reasons people hold cash in the first place. Economists have identified two basic reasons why people use currency. First, it is exceptionally convenient as a medium of exchange. Cash is easy to carry, it’s widely accepted, and it’s easy to divide for transactions of different sizes. Importantly, you can count on cash even when other payment methods might not be working, during power outages and natural disasters, for example. And cash has another advantage to users: It’s anonymous. Using cash keeps transactions away from the eyes of tax collectors, law enforcement agencies, and businesses that track the buying habits of individual Americans.

The second reason to hold cash is that it serves as a store of value. Keeping a hoard of currency—whether under a mattress, in a safe, or in a safe deposit box—is often viewed as a low-risk way to hold financial assets. That’s especially so during periods of political or financial turmoil. For example, during the recent financial crisis, some people may have withdrawn cash from accounts at banks and other institutions because they were afraid these institutions might fail. Around the world, during periods of political unrest or war, cash—especially the currency of a stable country like the United States—is seen as a safe asset that can be spirited out of harm’s way with relative ease.

Last and most certainly not least is the keystone effect of historically low interest rates. In the world of cash forecasting there is much debate on the topic of “lost opportunity cost”. Lost opportunity cost to the cash demand forecasting professional usually means interest and/or investment earnings that are lost or unavailable because capital is unnecessarily reserved as cash holdings. To the individual, company or government that is currently holding large denomination currency or contemplating converting capital to liquid currency that lost opportunity is measured as a combination of the income that capital could be earning if it were invested and the risk of leaving it exposed in an uncertain market.

Last and most certainly not least is the keystone effect of historically low interest rates. In the world of cash forecasting there is much debate on the topic of “lost opportunity cost”. Lost opportunity cost to the cash demand forecasting professional usually means interest and/or investment earnings that are lost or unavailable because capital is unnecessarily reserved as cash holdings. To the individual, company or government that is currently holding large denomination currency or contemplating converting capital to liquid currency that lost opportunity is measured as a combination of the income that capital could be earning if it were invested and the risk of leaving it exposed in an uncertain market.

Understanding the benefits and costs of holding currency helps clarify what causes the demand for cash to rise or fall. First, reflecting its role as a medium of exchange, cash holdings tend to rise as total spending in the economy goes up over time. Second, cash holdings tend to rise during periods of political and economic turbulence. Third, when the interest rate depositors can earn from a bank account goes up, the opportunity cost of holding cash is higher and people tend to hold less of it. Finally, increased availability of low-cost alternatives to cash will tend to shrink cash holdings, all else equal.

Lastly, I encourage all of you who are looking for any positive sign of the continuation and even growth of the cash industry to read this essay in its entirety. With the kind permission of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank and with the assistance of associates in the Cash Product Office, we offer a link to the downloadable version, here.

You can view Mr. Williams presentation in slide form here: